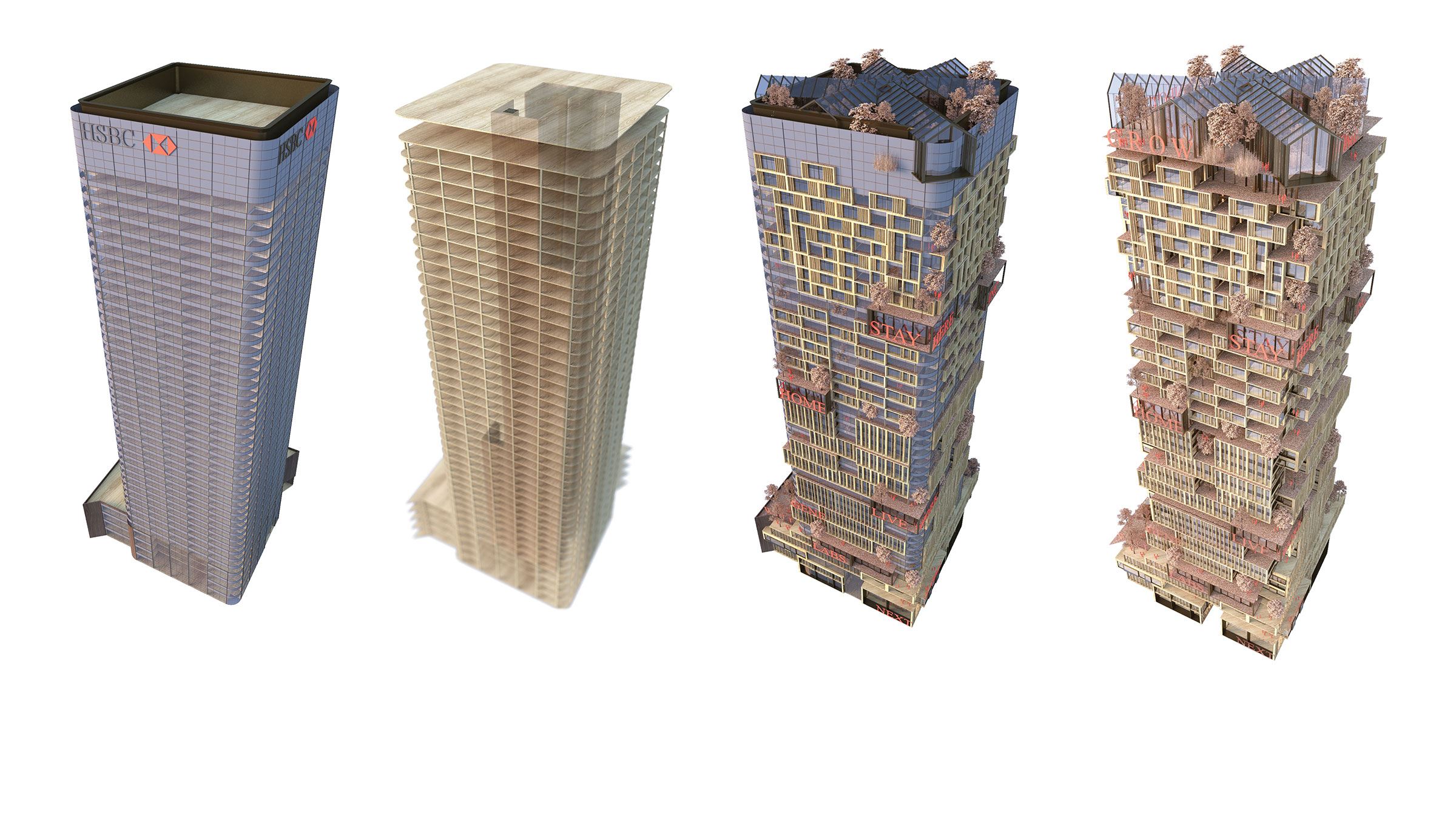

Cities around the world are struggling with office towers left empty from the pandemic and the shift to hybrid work. In London, HSBC Bank recently announced it will vacate 8 Canada Square, its 42-story headquarters building, by 2027. The move could leave a colossal city landmark completely empty in London’s once-booming Canary Wharf financial district.

Empty office towers drain neighborhoods of street life and place investors and cities in peril by cutting off lease and tax revenues. Residential conversion is often touted as a solution, but not all office towers lend themselves to easy residential retrofit. That is especially true for properties of the size and scale of the 8 Canada Square—a 1.6-million-sq.-ft. (164,000-sq.-m.) building with a central core and deep floor plate.

So, what might be done to position 8 Canada Square for future use and a return to maximum occupancy? David Weatherhead, design principal of HOK’s London studio, proposes transforming the building into a vertical neighborhood with a mix of uses and occupants. It’s a solution that could also apply to empty office towers across the globe. Here’s how:

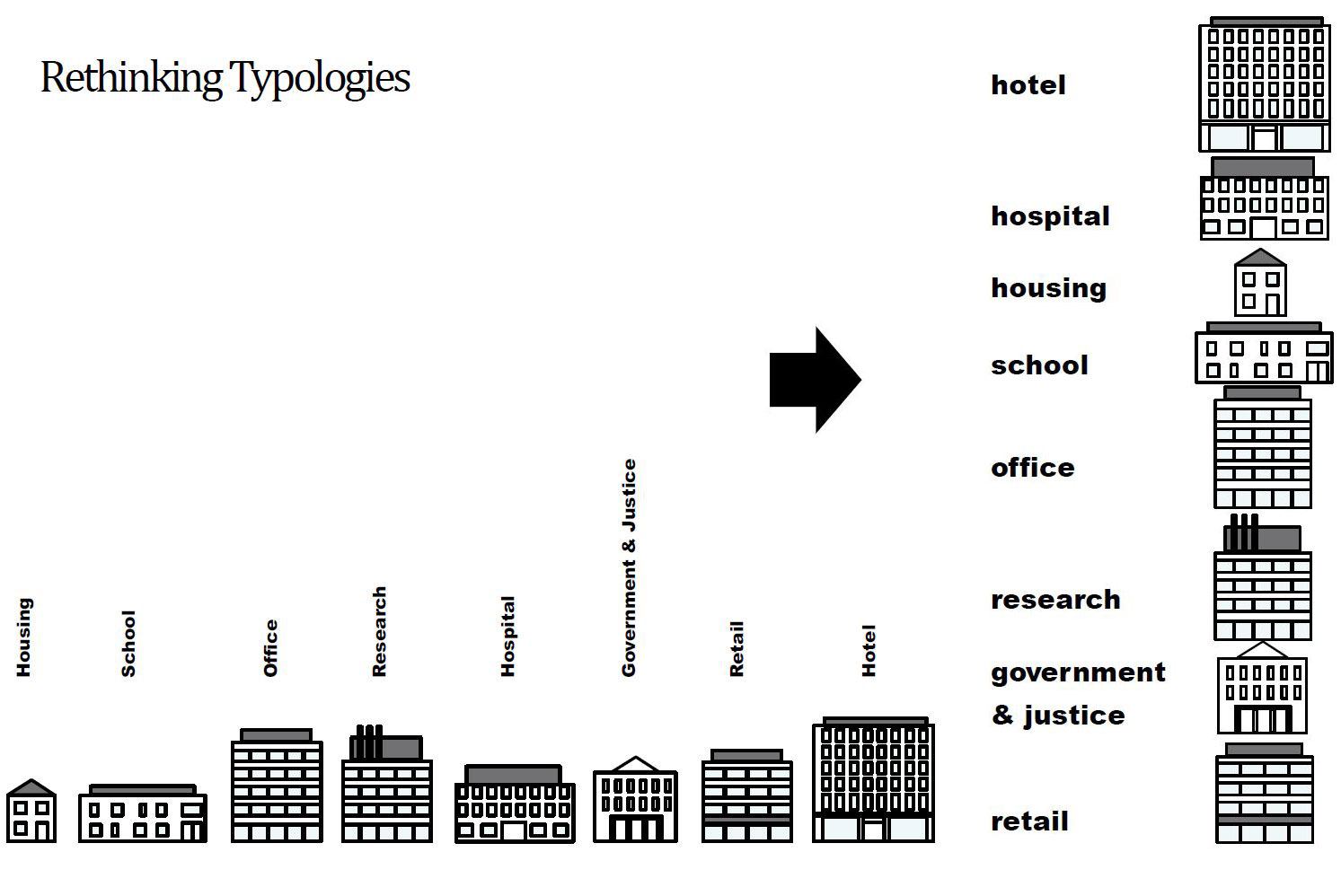

Reimagining the Standalone Office Building

For too long, downtowns and central business districts have prioritized office buildings over other building types. Yet a thriving urban core needs more than offices. It needs spaces for shopping, education, healthcare, government services, tourism, science, research and more.

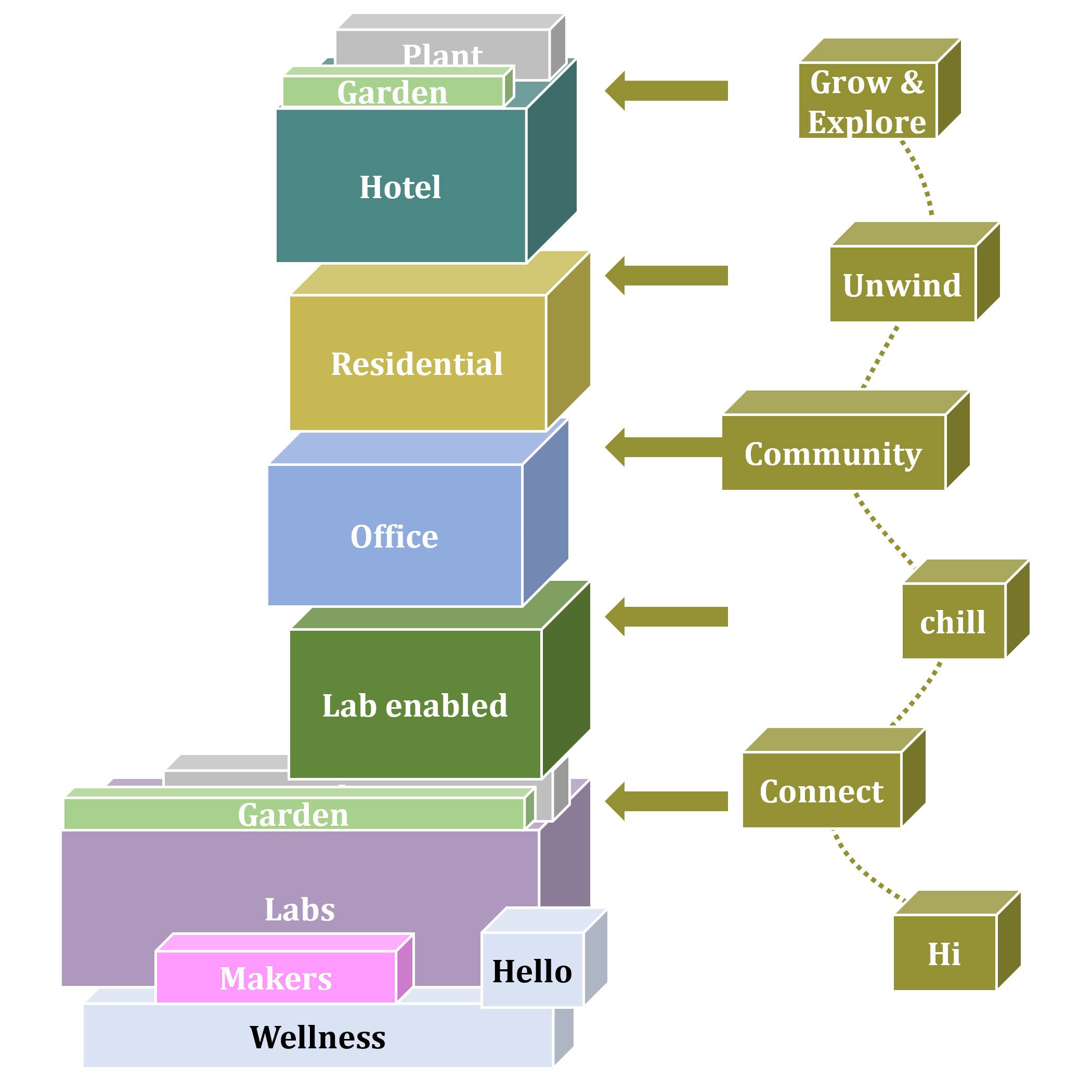

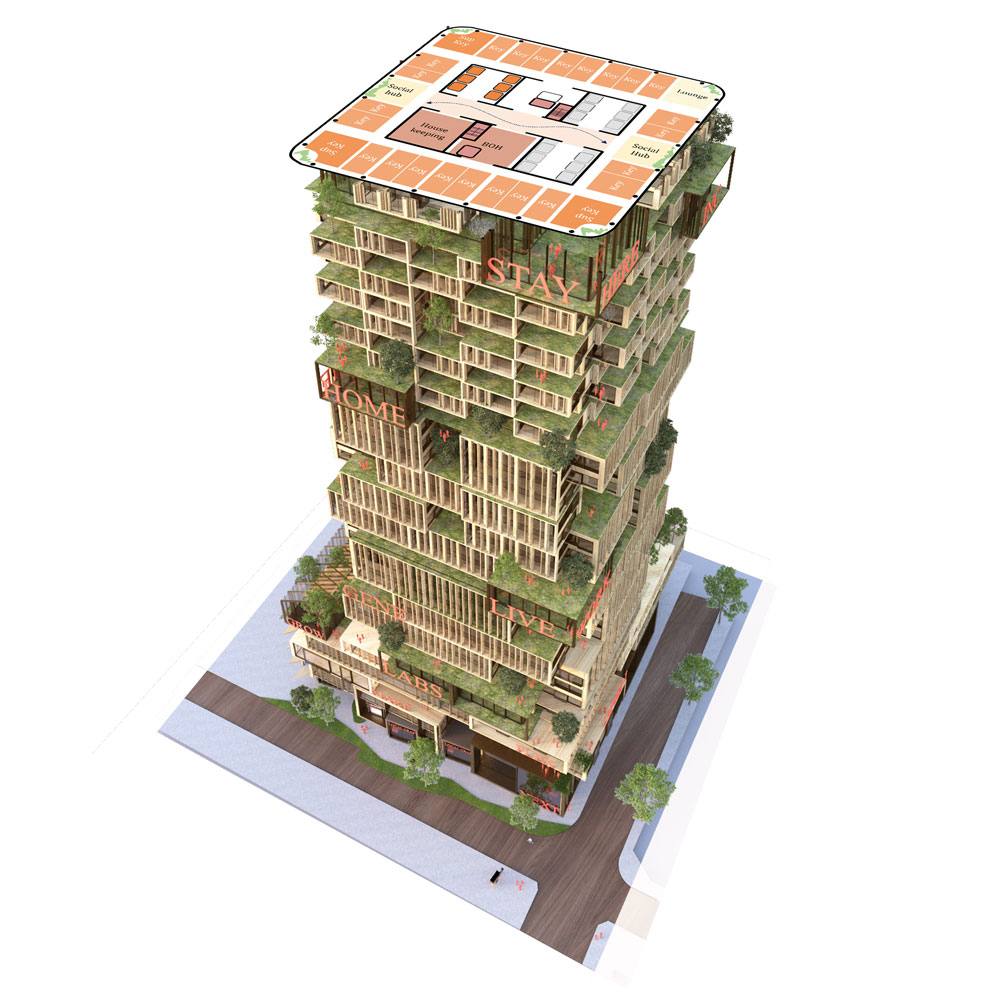

Buildings constructed as office towers could serve a variety of these uses by breaking the building into different zones and stacking them vertically.

Shared spaces between zones and at building entrances could connect building occupants, creating a sense of community, encouraging collaboration and promoting wellness.

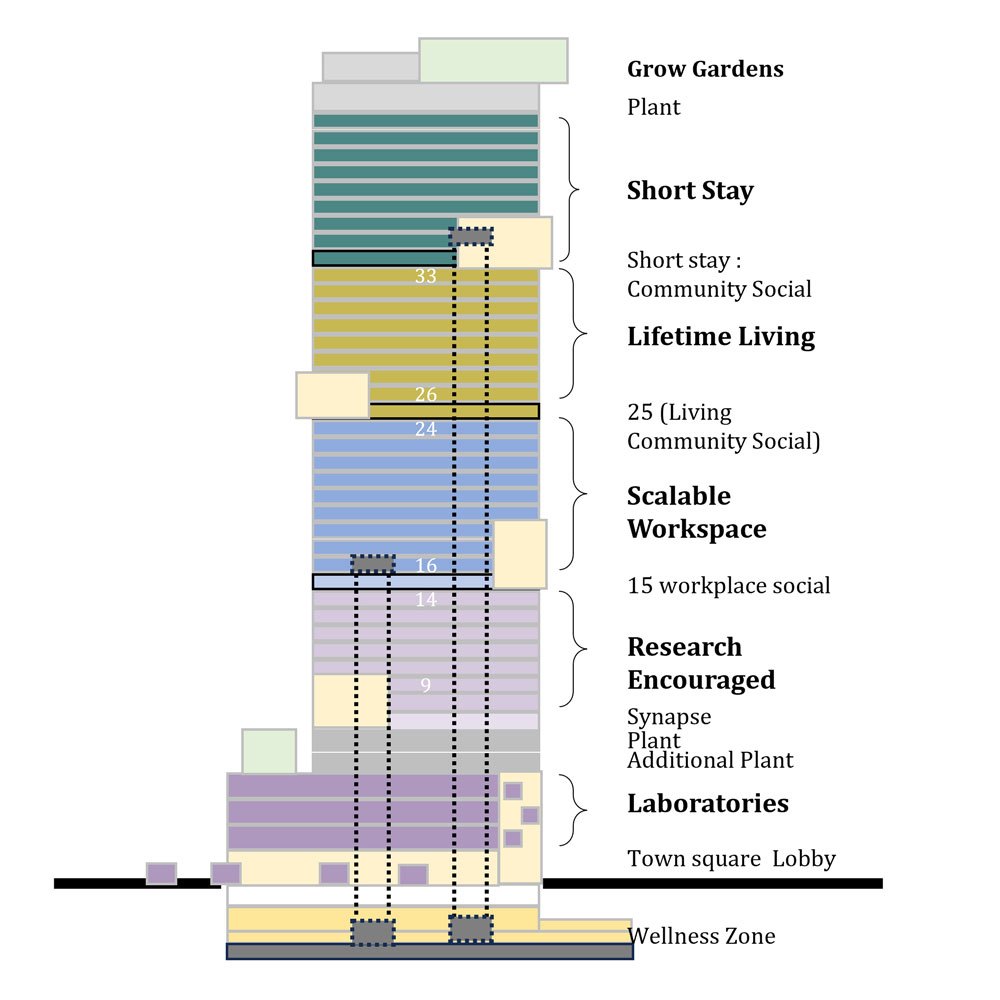

The images below explore this idea in theory (left) and practice as it could be applied to the 8 Canada Square.

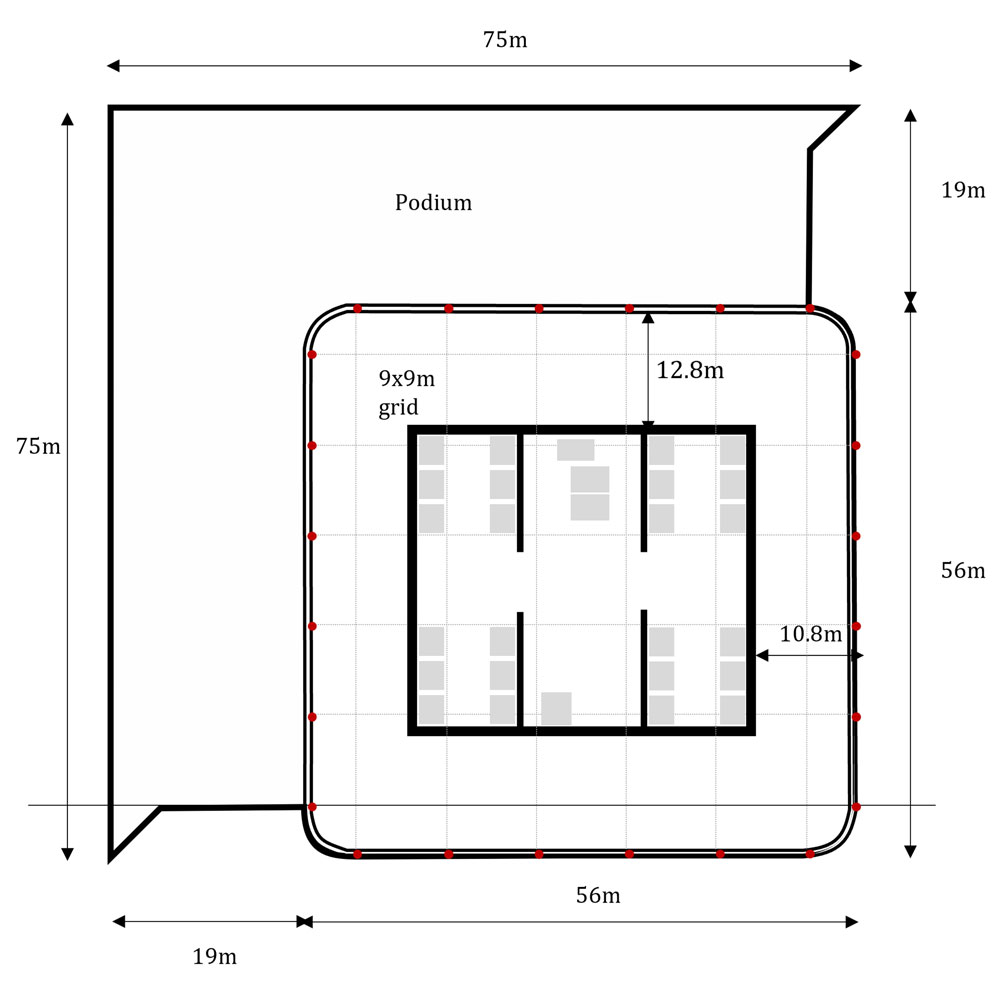

Two challenges of retrofitting a building like 8 Canada Square are that the structure has a relatively deep floor plate and a large structural core. Deep floor plates with central cores make it difficult to get natural light into the inner parts of the building, which is vital for residential use and occupant health and wellness.

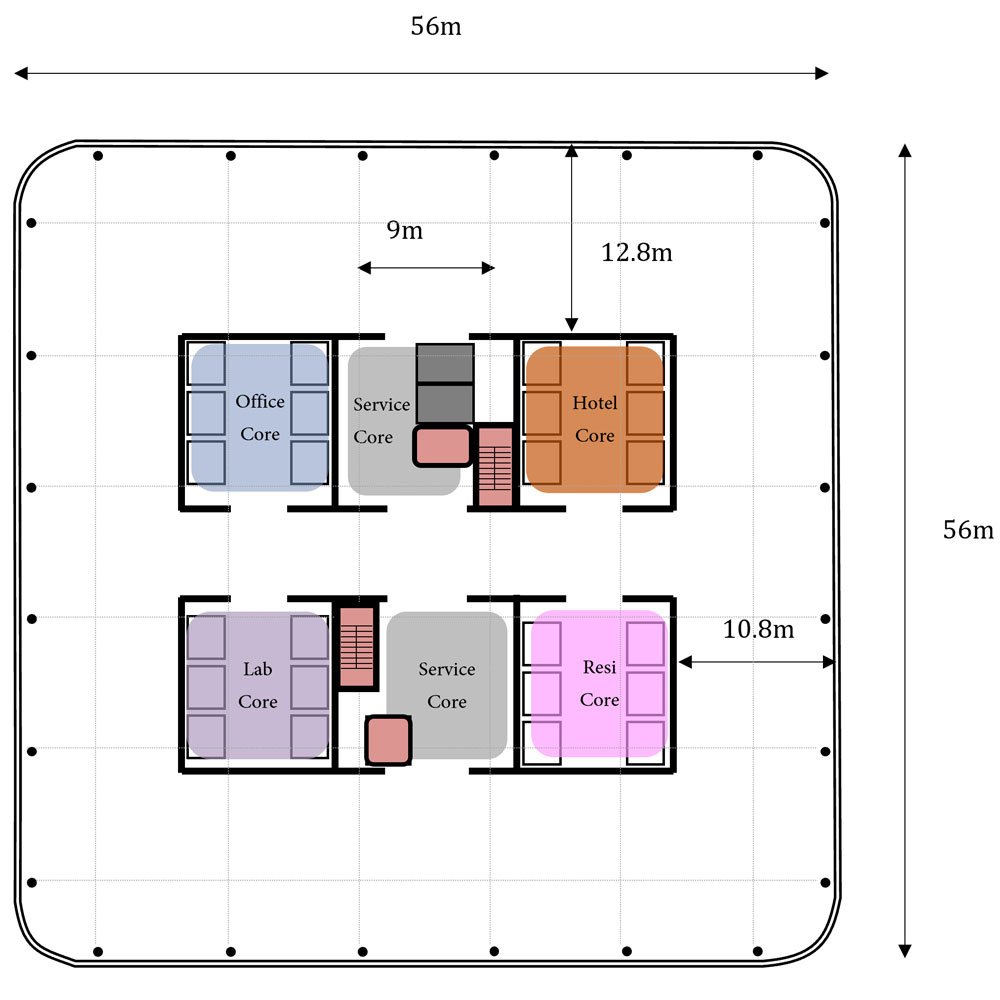

Aside from its four-story podium, 8 Canada Square measures 184 feet (56 meters) wide on each side. This suggests that daylight would need to travel a prohibitively long way (half the length of the building, 92 feet / 28 meters) to reach the centermost point of the building. Yet the tower’s interior isn’t quite as deep as it appears.

Four elevator banks in the central core push the building’s leasable space toward the perimeter of the building. On closer examination, the distance from the building’s shell to its structural core is a maximum of 42 feet (12.8 meters). This arrangement—coupled with the building’s generous floor-to-floor height of 13 feet (4 meters)—allows daylight to easily reach most occupied spaces within the building and opens the tower to various uses.

Let’s explore.

Repurposing 8 Canada Square

8 Canada Square’s four elevator banks allow the building to be segmented into four unique zones, each serviced by a dedicated bank of lifts. One could imagine 8 Canada Square broken into separate hotel, residential, office and lab zones.

Transfer floors between each zone could provide shared social and connection spaces for the tenants of each zone. Amenities on these floors could include reception, dining, gyms and lounge spaces.

Lab Zone

The building’s column-free work area and tall floor-to-floor height could accommodate ventilation and bench requirements for labs and scientific research.

Flues could be routed up the central core or through an unused elevator shaft.

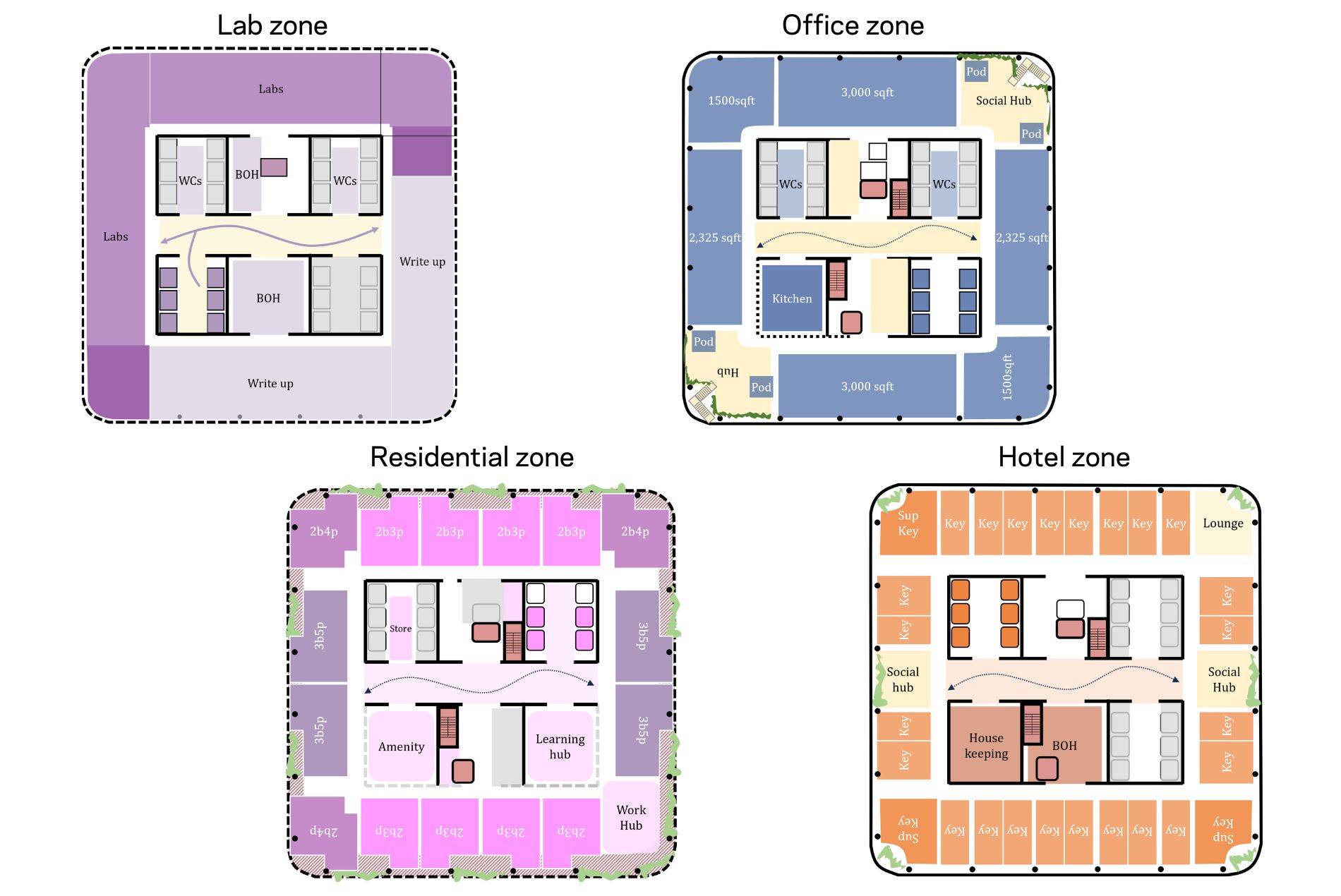

The scheme illustrated here imagines the floor plate split 60/40 for labs and writeup spaces.

Office Zone

The tower’s large floor plate also allows each level to be subdivided as offices for multiple tenants.

The scheme illustrated here shows a floor divided into six different offices of varying sizes. Shared amenities, such as restrooms and a kitchen, could be located in the elevator lobbies that do not service office floors. Opposite corners of the floor plate could be used as social and collaboration hubs with terraces and stairs connecting to other office levels.

Residential Zone

There is a need for more housing stock throughout London. The mid-upper levels of 8 Canada Square could be retrofitted (with some modification) to accommodate market-rate and affordable housing.

In the scheme illustrated here the floorplate is divided into two- and three-bedroom apartments with shared amenity and coworking space on each floor.

A new building facade would allow for recessed terraces that would improve daylighting within residential units and bring the building up to the residential code for fire safety and outdoor access. A new facade would also improve passive shading and overall thermal performance.

Hotel Zone

Canary Wharf is a destination for international and domestic business travelers, many of whom stay for more than just a night or two.

The top levels of 8 Canada Square—with impressive views of London and Canary Wharf—could be converted to a hotel or short-stay rentals. The floor plate allows for at least 32 generous-sized guest rooms. Social hubs and lounges on each floor could enable guests to mingle and host informal gatherings.

Community Access, Health & Well-Being

In addition to providing new space for residents, guests, workers and researchers, 8 Canada Square could open itself to the community as never before.

Today, the building’s lobby is closed to the public, and its podium promenade (right) is walled off in black metal—a stark contrast to the open and busy Canary Wharf tube station just across the canal.

Instead, what if the building’s ground floor and podium levels were activated with shops, dining, art and maker spaces as below?

Lower levels of the building could act like a town square, bringing building occupants into contact with the broader community.

See also: Maker Communities Above London’s Train Tracks

A building retrofit could also provide several ways to improve health and well-being, both for residents and the public. Rooftop gardens and greenhouses could provide local and sustainable food. Below grade, portions of the building’s car park could be transformed into a gym and fitness space and additional bike storage.

What’s Next

To be sure, none of the ideas outlined here are easy fixes. But they are achievable and could help ensure the long-term vitality of a London landmark. The same ideas shared here also could apply to hundreds of other office towers in cities worldwide.

Also worth mentioning are the financial and environmental savings of retrofitting a building compared to replacing it.

- Retrofits can be a less expensive option than building new.

- Retrofits cause less disruption to surrounding buildings with shorter build times.

- Retrofits are the best option when it comes to the environment and minimizing embodied carbon—the energy expended in the creation of concrete, steel and other building materials.

Want to know about retrofit opportunities and creating vibrant, mixed-use communities? Let’s connect!

Author David Weatherhead is a design principal in HOK’s London studio. His recent work includes the master plan for the Bollo Lane Mixed-Use Development, a TfL project that will transform underutilized land along the Piccadilly and District London Underground lines into a vibrant live-work community, and 10 New Bridge Street, a deep retrofit of an office building in the City of London which retains 75% of the building structure.