Ridership plummeted as people stayed home. Even with some states reopening, Amtrak’s ridership is still down 90 percent. The carrier, which relies on funding from the federal government, is significantly downsizing its operations and ending daily service to hundreds of stations across the U.S. for at least the next year.

But we will prevail over COVID-19 and one day be living in a post-pandemic world. Many public and private entities are advocating for resilient economic recovery plans that factor in sustainability, including in the transportation sector. Taking the train across the U.S. instead of a plane, for example, would cut that trip’s carbon dioxide emissions by about half. Analysts at Swiss bank UBS foresee a 10 percent reduction in global air travel growth compared to projections before the coronavirus outbreak, with an increased demand for the lower-carbon high-speed rail (HSR) alternative.

For now, passenger trains around the world are still running, albeit at much lower capacity. Train stations and carriers have put in place all sorts of health protocols to recapture the trust of travelers. There are limited bookings, one-way queuing systems, apps and signs for physical distancing, biometric check-in solutions, face covering requirements, contactless payment systems, protective plastic barriers, more stringent cleaning regiments and plenty of touch-free hand sanitizer. These strategies for reducing the exposure of passengers to infectious agents are likely here to stay.

Post-COVID-19: High-Speed Rail and Modern Train Stations

Even before the coronavirus pandemic pushed the federal budget deficit to record levels, budget cuts and policy stagnation posed significant investment challenges for the expansion passenger rail, which has long been plagued by aging infrastructure and a need for upgraded systems. “We still see concerted efforts from special interest groups to fight public transit including rail,” said William Kenworthey, HOK’s regional director of planning in New York. “The good news is that, especially in the denser parts of the country, people are starting to recognize the benefits of train travel—including high-speed systems.”

Once a COVID-19 vaccine is discovered and travel levels return to normal, we do expect to see a renewed interest in rail travel, including high-speed lines, as an alternative to airplanes and cars. Trains are a more cost-effective, environmentally friendly way of moving people between regional cities. More travelers are embracing them because they are faster, more comfortable and high-tech, and less susceptible to weather delays.

“People who travel abroad experience amazing high-speed rail systems. They come back and ask, ‘Why can’t we have that here?’”

“People who travel abroad experience amazing high-speed rail systems,” said Justin Wortman, a regional leader of Aviation + Transportation for HOK in Los Angeles. “They come back and ask, ‘Why can’t we have that here?’”

Generational trends are also playing a role. Millennials and Gen Zers are less interested in getting driver’s licenses than past generations and are buying fewer cars.

“Young people’s lives are more integrated with technology and they also have been more receptive to shared mobility,” added Wortman. “They are accustomed to getting Uber or Lyft rides on demand. They’re looking for a better travel experiences that are more enjoyable than driving long distances. Trains can provide that.”

As air travel returns following COVID-19, the ability to replace short-haul flights with train service would also help U.S. airports by relieving airspace congestion and enabling them to accept more profitable long-haul flights.

The Acceleration of High-Speed Rail

HOK’s master plan for Union Station (above) in downtown Washington, D.C., proposed ideas for transforming the station into a world-class center for high-speed rail and commercial activity.

Instead of flying, imagine jumping on a high-speed train to travel the 300 miles from Chicago to St. Louis. “You don’t have to travel from downtown to the airport,” said Peter Ruggiero, design principal for HOK in Chicago. “You don’t have to wait in long security lines. You can use unlimited Wi-Fi. Weather delays or turbulence are unlikely. You can enjoy a great meal. It can be an upscale but still casual experience. Yet the trip takes approximately the same amount of time as by air. It’s just a better way to travel that distance.”

Brian Jencek, San Francisco-based director of HOK’s planning group, was a frequent rider of the Shinkansen bullet train during his time working in Japan. “It made this soft, almost harmonic whistling noise as I gazed out the window and saw buildings and the landscape hurtle by at 200 miles per hour,” he said. “In just a few hours, we had left one culture behind in Tokyo and entered a completely new one in Osaka. Traveling by high-speed rail has a way of covering distances in a relaxed, almost magical way that isn’t possible with driving or air travel.”

That experience has remained a foreign concept to most Americans, especially those residing outside the Northeast Corridor. But that’s starting to change. Several high-speed rail systems intended to connect regional U.S. corridors are in various stages of operation and development. These include:

- Northeast Corridor: Stretching from Boston to Washington, D.C., the Northeast Corridor already has Amtrak’s Acela Express, which tops out at 150 mph yet averages about half that over the entire route. Though the coronavirus pandemic shut it down for a few months and it’s currently only operating a handful of weekday round trips, the Acela Express remains the closest thing the U.S. has to true high-speed rail (several lines in Europe and Asia top well over 200 mph). In this Northeast Corridor, more travelers use the train than fly. It has been a profitable line for the federally-funded Amtrak, which owns and operates most of the track. The company plans to replace its current Acela trains with 28 ultramodern, amenity-rich cars in 2021.

- Florida: Virgin Trains USA (formerly operating as Brightline) has launched a privately owned—the first in the U.S. in over a century—passenger rail system linking Miami to West Palm Beach. The company, even during the pandemic, continues to work on a 170-mile expansion to Orlando International Airport that will enable it to operate trains at up to 125 mph. With a station at PortMiami, Virgin Trains USA will be the first U.S. passenger rail system to link a major cruise port to an international airport.

- Southern California to Nevada: Virgin Trains USA subsidiary XpressWest is building a 170-mile high-speed rail passenger train system linking metropolitan Los Angeles to Las Vegas. With trains reaching 180 mph and connecting the cities with just a 90-minute ride, the line could be up and running by the end of 2023.

- Texas: A private venture called Texas Central Railway has plans to use all-electric Japanese Tokaido Shinkansen trains to whisk passengers the 240 miles between Dallas and Houston in fewer than 90 minutes, traveling at speeds of more than 200 mph. But cost escalations and complications created by the coronavirus have stalled those plans, and the company now is seeking the help of U.S. government stimulus money to get the project back on track.

- L.A. to San Francisco: Ambitious efforts to build a bullet train network stretching between Los Angeles and San Francisco, with links from the Central Coast, have been underway for more than a decade. Projects have been scaled back and repeatedly delayed by legal, budget, land procurement and political obstacles. The latest estimate is that the project could still go forward, but at a cost of at least $80 billion.

- Illinois: Several years ago the State of Illinois and Amtrak set out to build a $1.95 billion high-speed train linking Chicago and St. Louis. Though the project significantly upgraded the line’s locomotives, railcars and infrastructure, the top speed is still just 79 mph and, hindered by bureaucratic delays, the relatively modest goal of reaching 110 mph—half the speed of a Chinese bullet train—seems to still be several years off.

- Pacific Northwest: Microsoft is among the early backers of a potential 316-mile, high-speed rail system that would link Seattle, Portland and Vancouver.

“The ability to help lead and successfully deliver a complicated P3 project like this over several years will be key for designers of many rail systems and stations of the future."

Several of these rail projects demonstrate the opportunities for private investors to get involved as part of public-private partnerships.

“The ability to help lead and successfully deliver a complicated P3 project like this over several years will be key for designers of many rail systems and stations of the future,” said Kenworthey, who has been part of HOK’s team working on the redevelopment of LaGuardia Airport, one of the largest public-private partnerships in American history and the largest in U.S. aviation. “Design firms will need to be able to simultaneously balance the requirements of both public and private entities.”

One formidable challenge facing planners of U.S. high-speed rail systems is securing the land rights they need to succeed. “Other countries place more priority on mass transit and getting the direct routes they need to minimize travel time,” said Wortman. “The idea that community needs outweigh those of the individual is culturally more acceptable elsewhere.”

In the U.S., people often have to experience something before they can believe it, noted Jencek. “When it comes to investing in high-speed and even conventional rail, we have a huge learning curve to overcome and there is a responsibility to prove the value proposition to taxpayers,” he said. “If some of these high-speed rail initiatives underway across the country can succeed, people will begin to experience how amazing this mode of travel can be. When that happens, I’m confident they will want to build more.”

One Piece of a Network

Successful high-speed rail systems don’t exist in isolation. Instead, they’re part of an integrated transportation network that knits together city-level mass transit, regional rail and airports.

“Each mode plays an important role” said Carl Galioto, HOK’s president and managing principal of the firm’s New York and Philadelphia studios. “Regional rail can link major and secondary centers up to 500 miles apart. A true high-speed rail system can connect major urban areas 1,000 miles apart.”

As the convenience and comfort of passenger rail improve and these lines begin to have more direct connections to airports, opportunities for collateral commercial development around multimodal hubs begin to grow exponentially.

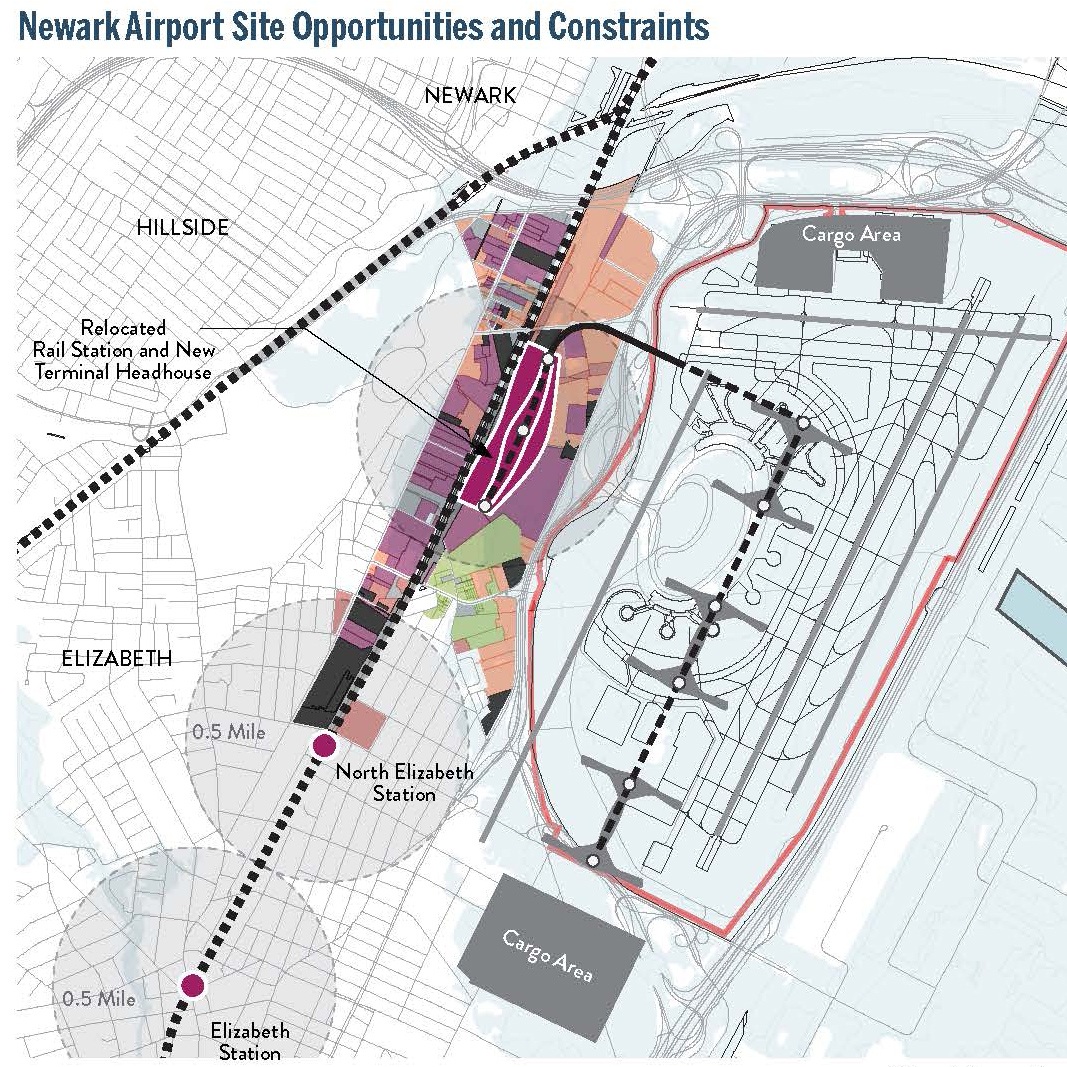

HOK recently collaborated with the New York Building Congress to author a report exploring the opportunities to transform Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) into an airport city with a multimodal transportation hub that includes high-speed rail.

Airport cities are mixed-use developments adjacent to airports. They often serve as hubs for companies looking to be near airports and have easy access to multimodal transport links and hospitality amenities. Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, which has office, retail and hospitality facilities as well as a subterranean railway station with a direct connection to the city center, is an oft-cited example of a successful airport city.

For the Newark Liberty report, HOK and New York Building Congress studied how one fully integrated multimodal transportation system could work. The plan proposes relocating the airport’s headhouse approximately a half a mile west and placing it directly over the Northeast Corridor rail line, where it would connect directly to regional and passenger trains and be less susceptible to rising sea levels from Newark Bay. The plan also encourages private investment by removing state and federal statutory and regulatory barriers to public-private partnerships.

“We envisioned an international airport with hundreds of acres of contiguous, underutilized land for mixed-use development,” said Galioto. “It would be resilient to climate change and offer direct connections to the local Port Authority PATH trains, NJ Transit’s commuter rail, Amtrak’s regional rail and Amtrak’s Acela high-speed rail.”

The plan includes a mixed-use residential neighborhood along the outer edge of the airport city. “Creating this residential edge would benefit the community and ultimately increase the economic value of the development,” said Kenworthey.

The Allure of Train Station Districts

In addition to airport cities, Jencek favors using train station districts to catalyze economic development. “Look no further than the train stations across Europe and Asia,” he said. “People want to live, raise their families and work near these stations. They are quieter and more accessible than airports.”

HOK’s plan for the Bay Meadows transit-oriented development (above) in San Mateo, California, connects each building parcel to a Caltrain station platform.

Designing rail systems and transit stations is a relatively straightforward process for an experienced team. To Jencek, though, the greater challenge is figuring out the right types of land use around a train station. “Think about an iPhone,” he said. “That tiny box packs all kinds of cellular data, memory, processors, cameras, apps, microphones and 100 other things. Developments around train stations are like iPhones. They combine a wide variety of uses in a way that the whole becomes much greater than the sum of its parts.”

Design Matters

In the spirit of grand, historic train stations like New York City’s Grand Central Terminal, the design of the Anaheim Regional Transportation Intermodal Center (above) celebrates the civic nature and sense of what a transportation center should be.

One reason President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation funding the construction of the U.S. Interstate Highway System in 1956 was to strengthen national security. He had seen Germany’s efficient network of high-speed roads while stationed there during World War II and believed it would allow for quick, transcontinental movement of population segments and troops. Yet President Eisenhower also had identified strong economic and social drivers for connecting cities with the newfound mobility afforded by automobiles. And he set about doing it the right way. “They hired extremely talented landscape architects and engineers to design that system,” said Ruggiero. “The original system was absolutely beautiful, with two parallel ribbons of concrete cutting through the American landscape.”

Ruggiero believes today’s citizens deserve this same level of attention when it comes to new passenger rail infrastructure and stations. “Taxpayers are asked to spend a lot of money on these projects,” he said. “We need to make an elegant, impeccable case for rail—and appearance matters. If it’s a first-class transportation system, everything about it should be geared toward creating a wonderful travel experience that lifts us all up.” Ruggiero points out, for example, that the designers of the New York City’s original Penn Station were inspired by the Baths of Caracalla in Ancient Rome.

“We need to show politicians, voters and private investors that a new transportation system will create a brighter future for the region,” said Jencek. “Designers have the vision to do this.”

An integrated team of planners and designers can create the most comprehensive—and beautiful—solutions. “There’s so much that a multidisciplinary firm can touch in terms of the impact on the landscape and the environment, the architecture, engineering and interior design, the passenger experience and the design of the infrastructure and adjacent commercial developments,” said Ruggiero. “The result is much better than when a team treats all the components as loosely connected silos.”

The key is to incorporate all the rigorous system requirements within a compelling design narrative that creates the right balance between those hard and soft systems. It should be a place people embrace, not just endure.

“It’s incredibly important to get the entire user experience right,” said Wortman. “Americans have many other transportation options and often don’t have much experience with travel by train. As designers, we can draw on our hospitality and placemaking expertise to make every part of the journey convenient, joyful and fun.”

More Than a Train Station

The train station of the future will be much more than a train station.

“The day is coming when we’ll stop thinking about these facilities as train stations, bus stations or airport terminals,” said Galioto. “They will be transportation centers where people can change modes between bikes, cars, buses, trains and planes. Designers need to create a seamless system that creates positive experiences for all travelers.”

One confidential North American airport is formulating plans to create a multimodal transit center to act as the city—and the region’s—“front door.” As the single point where travelers would arrive at the airport, check their luggage and pass through security, the facility would also serve as a hub for land-based modes of transit, including cars, rail and bus. It would ease congestion and streamline travel across the region.

“There’s no doubt that airports will increasingly become central transportation hubs for the communities they serve,” added David Mason, regional leader of Aviation + Transportation for HOK in Dallas. “Combining all modes of transportation into one location maximizes each method, thereby leveraging all of them for the greatest benefit to travelers.”

As the lines blur between train stations, bus depots, airports and even cruise ship terminals as that industry recovers from the pandemic, these facilities will start to look and feel more alike, with many functions becoming automated.

Security monitoring systems, for one, will take a quantum leap forward over the next decade. In the 1990 movie “Total Recall,” high-tech body scanners at the airport security checkpoint verified the identity of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character as he moved. The artificial intelligence (AI)-powered transportation facility systems of the future will increase the use of biometrics and facial recognition software to make the passenger screening process faster, more transparent and more effective.

Passengers who spend less time waiting in security checkpoint lines will enjoy a more relaxing experience and be able to spend more time—and money—on retail and concessions in the stations. As passenger dwell times get longer, train stations will have more opportunities to broaden and expand their offerings.

“Train travel in the U.S. has historically been very function-driven,” said Wortman. “But with a rise in ridership, we’ll be able to introduce more robust amenities that pique passengers interest. Could they have a business meeting, shop, exercise, get their nails done or meet friends for a meal? It’s almost like black box theater design. We will create an invisible armature that is ultra-flexible to accommodate different uses.”

As they morph into places that function as much more than transit stations, these facilities will become even more entrenched in and valuable to their communities. “Look at Grand Central Terminal (below) in Manhattan,” said Ruggiero. “It’s now 107 years old and is as viable today as the day it opened. Transportation facility owners should be thinking in terms of incorporating multiple uses and aiming for 100-plus-year lifespans for these buildings. Durability and longevity like that come from thoughtful design and investing upfront in the right places.”

If We Can Land on the Moon

More high-speed rail projects will succeed as federal and state government groups collaborate with private investors and local communities to overcome the inherent budget, statutory, regulatory, seismic, land rights-of-way and, with the advent of COVID-19, public health challenges. Then, train by train, new systems will be built and communities will experience tangible results.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy delivered a speech at Rice University in which he proclaimed to the world that the U.S. would send people to the Moon, almost 239,000 miles away, by the end of the decade. “If we were able to land on the moon in just seven years, don’t tell me we can’t get a train to go 200 miles per hour in this country,” said Ruggiero. “It’s coming.”